What exactly is Temperature ? A statistical picture

What exactly is temperature?, well, Temperature is a physical quantity that quantitatively expresses the attribute of hotness or coldness. Temperature is measured with a thermometer. It reflects the average kinetic energy of the vibrating and colliding atoms making up a substance.

This is a type of definition we found normally. Here, I want to show you a view of temperature from the point of view of Statistical Mechanics. So, let's see that,

Introduction to Macrostates and Microstates

To understand what these means, we will see an example.

Consider a box of identical coins(\(5\)). Now, just close the lid of the box and give the box a nice shake. This will shuffle all the coins. Now, if we see inside the box, we will see some of the coins with head(\(H\)) pointing up and some with tail(\(T\)). There are \(2^{5}\) possible configuration.

As we know from probability theory, all of these states are equally likely. So, each state have the probability of \(1/2^{5}=2^{-5}\). We say, each of the configuration a Microstate of the system. See the table below,

| No. | Microstate (No. of Heads, \(H\)) | Microstate Combination |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | H = 0 | TTTTT |

| 2 | H = 1 | HTTTT |

| 3 | H = 1 | THTTT |

| 4 | H = 1 | TTHTT |

| 5 | H = 1 | TTTHT |

| 6 | H = 1 | TTTTH |

| 7 | H = 2 | HHTTT |

| 8 | H = 2 | HTHTT |

| 9 | H = 2 | HTTHT |

| 10 | H = 2 | HTTTH |

| 11 | H = 2 | THHTT |

| 12 | H = 2 | THTHT |

| 13 | H = 2 | THTTH |

| 14 | H = 2 | TTHTH |

| 15 | H = 2 | TTTHH |

| 16 | H = 3 | HHHTT |

| 17 | H = 3 | HHTHT |

| 18 | H = 3 | HHTTH |

| 19 | H = 3 | HTHTH |

| 20 | H = 3 | HTTHH |

| 21 | H = 3 | THHTH |

| 22 | H = 3 | THTHH |

| 23 | H = 3 | TTTHH |

| 24 | H = 4 | HHHTH |

| 25 | H = 4 | HHTHH |

| 26 | H = 4 | HTHHH |

| 27 | H = 4 | THHHH |

| 28 | H = 5 | HHHHH |

See, here Microstate Combination has \(5\) symbols. The first symbol represent face of first coin, second symbol represent face of second coin and all. So, see serial No. \(16\) (\(HHHTT\) ), there \(1^{st}\), \(2^{nd}\) and \(3^{rd}\) coins are showing heads and last two are showing tails. This exact information of each particle is called Microstate. So, to identify a microstate, we need to identify each coin's state individually.

But do we really do this?, Nope! Normally, we just see the number of heads or tails, i.e., we normally categorize the outcome of this shaking box experiment by simply counting the number of coins which are haeds and which are tails (eg: in No. \(16\) we have \(3\) heads and \(2\) tails). This categorization is called Macrostate.

So, from our table, \(H=2\) and \(T=3\) is a macrostate and under this (from serial no. \(7\) to \(15\)) macrostate, we have \(9\) microstates.

Let's say, we have \(N=100\) coins in the box. Then,The macrostate of \(50H\) and \(50T\) has \(100!/(50!)^2 \approx 10^{29}\) microstates.

The macrostate of \(53H\) and \(47T\) has \(100!/(53!)(47!) \approx 8\times 10^{28}\) microstates.

The macrostate of \(100H\) and \(0T\) has \(100!/(100!)(0!) =1\) microstate.

So, the key points we notice is that,

The system could be described by a very large number of equally likely microstates.

What we actually measure is a property of the macrostate (like number of heads in our example) of the system.

The macrostates are not equally likely, the microstates are so. As a result, the macrostate with highest number of microstate is the state of the system. (see the video below from 11:31)

Temperature as a Statistical Artifact

Microstates and macrostates also exist in thermal systems. Just like our coin example, thermal systems have a hidden statistical aspect. To specify a microstate for a thermal system, we would need to know the microscopic configuration of every individual atom in the system, such as their positions, velocities, or energy. In practice, it is impossible to measure the exact microstate of the system.

The macrostate of a thermal system, on the other hand, can be described by measurable quantities like pressure, energy, or volume.

Because of this, we don’t concern ourselves with determining the exact microstate. Instead, we assume that for a system with energy \(E\), there are \(\Omega(E)\) equally likely microstates that the system could be in. This number is normally huge.

Building the system

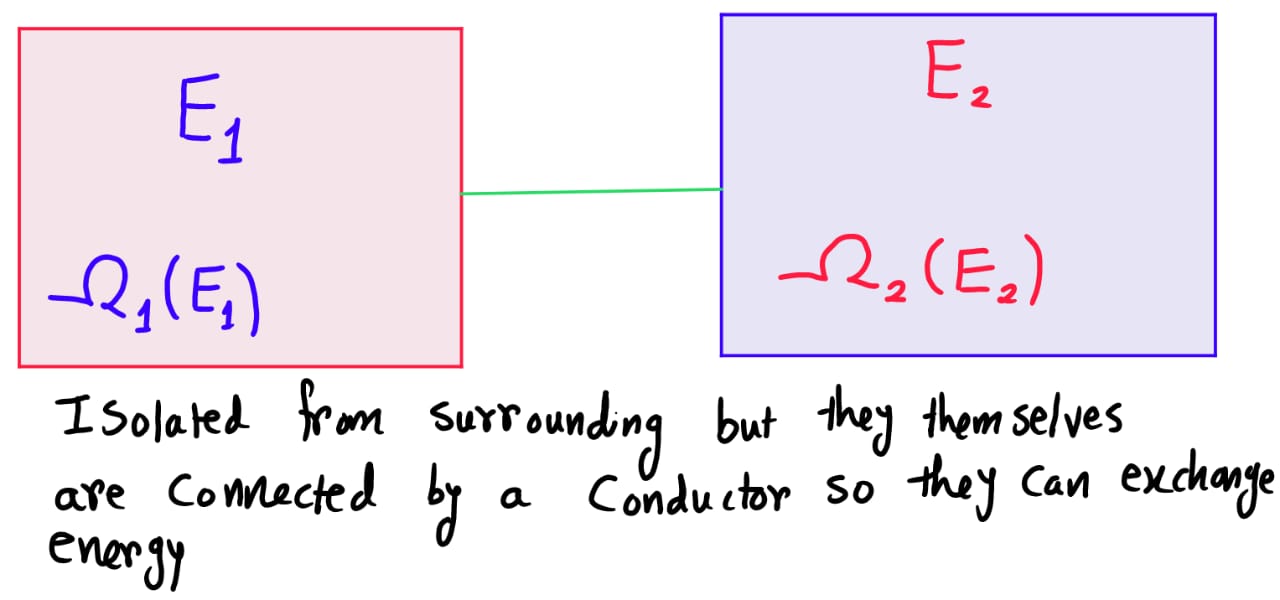

Suppose, we have two large systems that can exchange energy with each other but they can't exchange energy with surrounding(we the image below).

The system can be in anyone of these possible microstates right?... Nope!

Remember, the systems are able to exchange energy with each other and let's assume that they have been left in the condition of being connected together for a sufficiently long time that they have come into thermal equilibrium. This implies, \(E_1\) and \(E_2\) have come to fixed values.

Maximizing microstates and Temperature defn

As previously discussed, the system will choose to maximize the microstate number. So, let's maximize \(\Omega(E_1,E_2)\).

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{d}{dE_1}(\Omega(E_1,E_2)) &= 0 \\ \Omega_2(E_2)\frac{d \Omega_1(E_1)}{d E_1} + \Omega_1(E_1)\frac{d \Omega_2(E_2)}{d E_2} \frac{d E_2}{d E_1}&= 0 \end{aligned} \]Using \(dE_1 = - d E_2\), we will have,

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{1}{\Omega_1(E_1)}\frac{d \Omega_1(E_1)}{d E_1} &= \frac{1}{\Omega_2(E_2)}\frac{d \Omega_2(E_2)}{d E_2} & = \textit{constant}\\ \frac{d \ln(\Omega_1)}{d E_1}&= \frac{d \ln(\Omega_2)}{d E_2} &= \textit{constant} \end{aligned} \]This condition defines the most likely division of energy between the two systems if they are allowed to exchange energy since it maximizes the total number of microstates. But we know equilibrium means being in the same temperature. So, the constants are function of temperature.

This tells us:

\[ \begin{aligned} \frac{1}{\Omega(E)}\frac{d \Omega(E)}{d E} &= \frac{1}{k T}\\ \frac{d \ln(\Omega(E))}{d E} &= \frac{1}{k T} \end{aligned} \]where \(k\) is the Boltzmann constant (we will use natural unit, hence setting \(k=1\)).

So, now we have the definition but is that all?, actually yes!

Just using the microstate number, we can find temperature of the system and also see how temp of two system comes to equilibrium.

Simulation

Let's use this idea and simulate few models. We will see how the the microstates along can define everything.

We will start with a model where \(\Omega \propto E^3\). Let's first define all the functions we need.

using Random, ForwardDiff

function omega1(E)

return E^3

end

function omega2(E)

return E^4

end

function temperature1(E)

g = x -> ForwardDiff.derivative(x -> log(omega1(x)), x)

return 1 / g(E)

end

function temperature2(E)

g = x -> ForwardDiff.derivative(x -> log(omega2(x)), x)

return 1 / g(E)

endNow, let's write a function for simulation.

function heat_transfer(E1, E2, steps)

energies_1 = [E1]; energies_2 = [E2]

temperatures_1 = [temperature1(E1)]

temperatures_2 = [temperature2(E2)]

for step in 1:steps

δE = 0.1

if (E1 - δE >= 0) && (E2 + δE >= 0)

T1 = temperature1(E1)

T2 = temperature2(E2)

if T1 > T2

E1 -= δE; E2 += δE

elseif T2 > T1

E1 += δE; E2 -= δE

end

push!(energies_1, E1); push!(energies_2, E2)

push!(temperatures_1, temperature1(E1))

push!(temperatures_2, temperature2(E2))

end

end

return energies_1, energies_2, temperatures_1, temperatures_2

endNow, let's run the simulation.

E1 = 10.0; E2 = 5.0

steps = 100

energies_1, energies_2, temperatures_1, temperatures_2 = heat_transfer(E1, E2, steps)

plot(energies_1, label="Energy of Body 1 (E1)", xlabel="Steps", ylabel="Energy", lw=2,title="Energy Transfer between Bodies")

p1 = plot!(energies_2,lw=2, label="Energy of Body 2 (E2)")

savefig(p1, joinpath(@OUTPUT, "plotlytemp_stat01.json"))

plot(temperatures_1, lw=2, label="Temperature of Body 1 (T1)", xlabel="Steps", ylabel="Temperature", title="Temperature Equilibration between Bodies")

p2 = plot!(temperatures_2,lw=2, label="Temperature of Body 2 (T2)")

savefig(p2, joinpath(@OUTPUT, "plotlytemp_stat02.json"))Let's see the plots: For the energy we can clearly see both bodies's energy are not equal in equilibrium as their specific heats are different (verify that their specific heats are different).

But as expected in their equilibrium, their temperatures are same.Before ending let's see one more example. Suppose, we have a box of coins and number of heads represent the energy of the system (This is wrong as energy is not constant, but still it will give you some idea for the problem below).

Then, let's write the code:

using Plots;plotlyjs()

function omega(N::Int, k::Int)

return binomial(BigInt(N), BigInt(k))

end

function temperature(N, k)

if k == 0 || k == N

return Inf # Avoid division by zero at boundaries

else

return 1 / (log(omega(N, k + 1)) - log(omega(N, k)))

end

end

function entropy(N, k)

return log(omega(N, k))

end

function simulate_coin_toss(N)

energies = 0:N

microstates = [omega(N, k) for k in energies]

temperatures = [temperature(N, k) for k in energies]

entropies = [entropy(N, k) for k in energies]

return energies, microstates, temperatures, entropies

end

function plot_results(N)

energies, microstates, temperatures, entropies = simulate_coin_toss(N)

p = plot(layout = (3, 1), size = (1200, 1800))

p = plot!(energies, microstates, lw=2,label="", xlabel="Energy (Number of Heads)", ylabel="Microstates (Ω)", title="Microstates (Ω)", subplot=1)

p = plot!(energies, temperatures, lw=2,label="", color=:red, xlabel="Energy (Number of Heads)", ylabel="Temperature (T)", title="Temperature (T)", subplot=2)

p = plot!(energies, entropies, lw=2, color=:green,label="", xlabel="Energy (Number of Heads)", ylabel="Entropy (S)", title="Entropy (S)", subplot=3)

return p

endNow, let's plot this:

p = plot_results(50)

savefig(p, joinpath(@OUTPUT, "plotlytemp_stat1.json"))Hope this helps you in some way. If you like it then share with others if possible.

If you have some queries, do let me know in the comments or contact me using my using the informations that are given on the page About Me.