Hidden Pi inside Mandelbrot Set

Mandelbrot Set and \(\pi\) both are amoung the most famous things of mathematics. I mean, most of the people who loves reading maths stuff have atleast heard about this two. But have you imagined a way we can combine these two?

Our goal today is to see how this two are related.

A poem of \(\pi\) and mandelbrot set

In realms where numbers twist and twine,

Pi and Mandelbrot align.

Pi, with digits endless, pure,

A constant rhythm to endure.

Mandelbrot’s fractals, wild and vast,

Patterns in a boundless cast.

Together, they reveal the lore,

Of nature's dance, forevermore.

In infinite math, their beauty lies,

A timeless waltz beneath the skies.

Introduction to Mandelbrot Set

Before starting let's first reacp what is Mandelbrot Set?

In the most simple term, The mandelbrot set is the set of all complex numbers \(c\) for which \(f_c(z)=z^2+c\) doesn't goes to infinity when iterated from \(z=0\).

Let's try to understand it using a example.

Suppose, we have a number \(c=1\). I want to know if it's inside the mandelbrot set, then we start with \(f_c(z) = f_1(z) = z^2+1\).

Then,

We start with \(z = 0\) and put it into \(f_1(z)\) which gives us \(f_1(z=0)=1\).

Then, we set the result \(1\) as \(z_1 = 1\) and use it as the new input of \(f_1(z)\). This gives us \(z_2 = f_1(z_1) = f_1(f_1(0)) = 1^2+1=2\).

In theory we repeat this process for infinite number of times. If the output goes to infinity, then the number is not inside mandelbrot set. In our case the results are \({1,2,5,26,\cdots}\), i.e., it keeps on increasing. So, \(c=1\) is not inside mandelbrot set.

If we had taken \(c=-1\), then the values would have been \(0,-1,0,-1,\cdots\). This is a oscillating series. As a result it will never grow towards infinity.

Hence, \(-1\) is an element of the mandelbrot set.

I hope this idea is now clear. It should be clear that \(c\) can be any imaginary number. There is no restriction that says \(c\) must be real.

Let's see a code for checking if a number is inside the set. Here we will check the iteration outputs upto \(1000^{th}\) iteration as in code we can't check upto infinite iteration.

function mandel_check(c,max_ita=1000)

z = 0

for i in 1:max_ita

z = z^2 + c

if abs(z) >= 2

print(c," is not in mandelbrot set upto set iter no.")

break

else

if i==max_ita && abs(z)<2

print(c," is in mandelbrot set upto set iter no.")

end

end

end

end

mandel_check(1)The output is:

1 is not in mandelbrot set upto set iter no.mandel_check(0.3+0.2im)0.3 + 0.2im is in mandelbrot set upto set iter no.Pi hidden in Mandelbrot Set

Around \(1991\), Dave Boll found experimentally a strange connection between pi and the Mandelbrot set. According to the letters, he was trying to show that the neck of the mandelbrot set at \((-0.75,0)\) is actually of \(0\) thickness (Don't ask me how there was a google chat on \(1991\) when google itself started around \(1998\)).

He described that we while he was trying to see how many iteration are needed for \(c = -0.75 + \mathbb{i}\epsilon\) so that \(f_c(z) = z^2 + c\) goes out of the mandelbrot set. Here is a table:

| \(\epsilon\) | # of iteration |

|---|---|

| 1 | 3 |

| 0.1 | 33 |

| 0.01 | 315 |

| 0.001 | 3143 |

| 0.0001 | 31417 |

| 0.00001 | 314160 |

| 0.000001 | 3141593 |

and so on. WoW!!... Are those digits of pi! what the heck!

Rather than \(c= -0.75 + \mathbb{i} \epsilon\), let's see the point \(c = 0.25 + \epsilon\). We are going to use this as it's real and that makes the visulization a bit easy.

Let's see the table for this \(c = 0.25 + \epsilon\).

| \(\epsilon\) | # of iteration |

|---|---|

| 0.1 | 8 |

| 0.01 | 30 |

| 0.001 | 97 |

| 0.0001 | 312 |

| 0.00001 | 991 |

| 0.000001 | 3140 |

| 0.0000001 | 9933 |

| 0.00000001 | 31414 |

| 0.000000001 | 99344 |

| 0.0000000001 | 314157 |

Again, we see the same pattern but only for \(\epsilon = 10^{-2n}\) where \(n\) is some positive integer including \(0\).

Let's write a code to verify this:

function cal_pi(epsilon)

setprecision(300)

c = BigFloat(0.25) + BigFloat(epsilon)

z = BigFloat(0.0)

steps = 0

while abs(z)<2

z = z^2 + c

steps += 1

end

return steps

endHere the function takes \(\epsilon\) as input.

epsilon = 0.01

print("For epsilon = ",epsilon," irter needed = ",cal_pi(epsilon))The output is

For epsilon = 0.01 irter needed = 30If we needs \(n\) digits of \(\pi\), we can write the code as,

n=7

epsilon = BigFloat(1/10^(2*n))

print("Approx n = ",n," correct digits of pi = ",cal_pi(epsilon))which gives,

Approx n = 7 correct digits of pi = 31415925But why does it works?, let's try to find that out!...

Why it works?

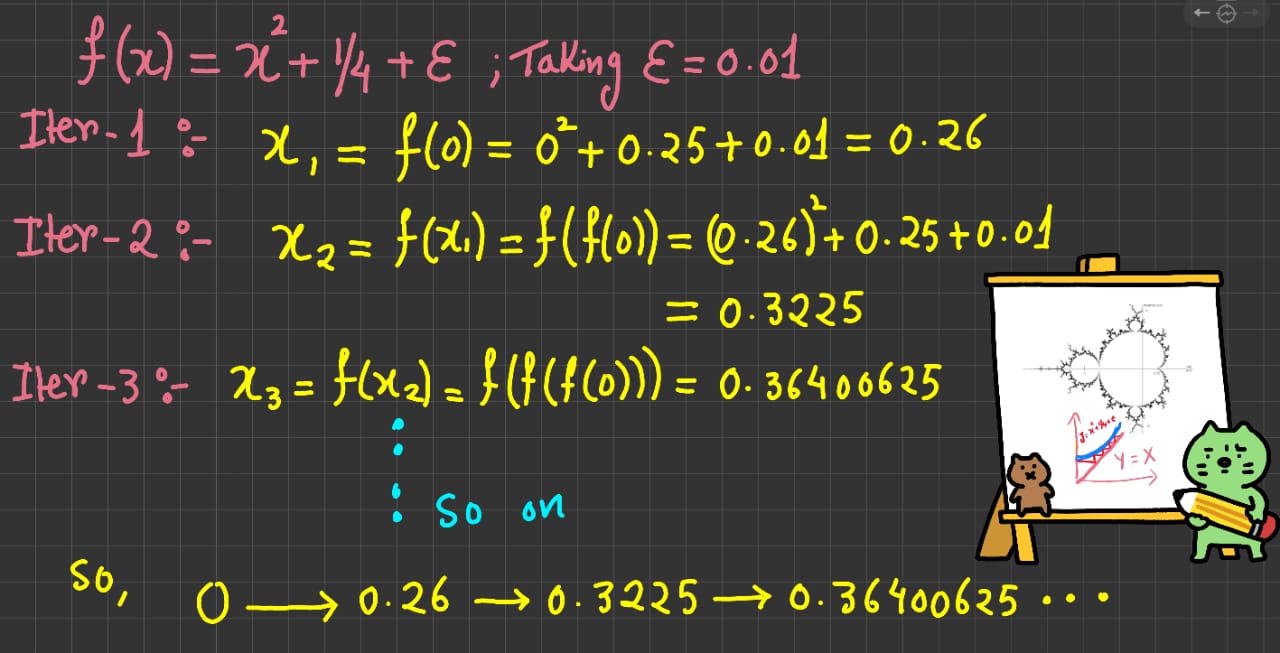

As we are seeing this for \(c = 1/4 + \epsilon\) and it is real. Hence, all the later iterative outputs are going to be real. So, let's take \(x\) in place of \(z\)(Here is a image showing few initial real outputs).

So, we have ,

\[ f(x) = x^2 + \frac{1}{4} + \epsilon \]we will start with \(x=0\) and do the iteration.

The function is just a parabola. It's plot it as it will give us insight.

Here the slider represent the values of \(\epsilon\). It starts with \(\epsilon = 0\). The black line here represent \(y=x\). But why we have added this?

The answer is simple. Let's understand it in following steps.

We start the iteration with \(x=0\). This represent the point \((0,1/4 + \epsilon)\).

Then, we take \(f(0) = 0^2 + 1/4 + \epsilon\), which is our y-coordinate as the new input. So, basically, we are converting this \(y\) into \(x\). This is done by drawing a line parallel to the x-axis.

The new input is then the x-axis of the intersection of that green line and \(y=x\). To represent that we draw a line parallel to the y-axis until it hits the parabola.

Then we repeat the process.

This visually shows us the iteration and hence we need \(y=x\) line.

Play with the slider and change the value. You will see how the iteration goes to infinity (although to save computation power, the iteration number can only go upto 20).

Now, we can write,

\[ x_{k+1} = x_k^2 + \frac{1}{4} + \epsilon \text{ with } x_0 = 0 \]which can be written as

\[ x_{k+1} - x_k = \Big( x_k - \frac{1}{2} \Big)^2 + \epsilon \text{ with } x_0 = 0 \]This can be approximated as,

\[ \frac{dx}{dt} = \Big(x - \frac{1}{2}\Big)^2 + \epsilon \text{ with } x(0) = 0 \]for \(\epsilon\) small and \(x\) very close to \(1/2\).

Let us define \(T(\epsilon)\) which represent the time, it takes for \(x(t)\) to reach 2. Here we are curious about reaching \(2\) as this is the value which tells us if \(x(t)\) is inside mandelbrot set or not.

Using mathematica,

DSolve[{y'[x] - (y[x] - 1/2)^2 == \[Epsilon], y[0] == 0}, y, x]The output is,

{{y -> Function[{x},

1/2 (1 +

2 Sqrt[\[Epsilon]]

Tan[x Sqrt[\[Epsilon]] - ArcTan[1/(2 Sqrt[\[Epsilon]])]])]}}So, we have,

\[ x(t) = \frac{1}{2} + \sqrt{\epsilon} \tan\Big( t\sqrt{\epsilon} - \arctan(1/2\sqrt{\epsilon}) \Big) \]This can be rewritten as,

\[ t\sqrt{\epsilon} = \arctan \Big( \frac{x(t) - 1/2}{\sqrt{\epsilon}}\Big) + \arctan\Big( \frac{1}{2\sqrt{\epsilon}} \Big) \]Taking the limit if \(\epsilon \to 0\),

\[ \lim_{\epsilon \to 0^+}T(\epsilon)\sqrt{\epsilon} = \lim_{\epsilon \to 0^+}\arctan \Big( \frac{x(t) - 1/2}{\sqrt{\epsilon}}\Big) + \lim_{\epsilon \to 0^+}\arctan\Big( \frac{1}{2\sqrt{\epsilon}} \Big) \]This reduces to,

\[ \lim_{\epsilon \to 0^+}T(\epsilon)\sqrt{\epsilon} = \pi \to T = \lim_{\epsilon \to 0^+} \frac{\pi}{\sqrt{\epsilon}} \]This tells us that for \(\epsilon = 10^{-2n}\), we will give us \(n\) digits of \(\pi\).

If you want to read the official published proof (which is very different from mine), then visit here . __________________________________________________

I hope you learn something new and enjoyed this article.

If you have some queries, do let me know in the comments or contact me using my using the informations that are given on the page About Me.